Following in the footsteps of Me Talk Pretty One Day and Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim, the latest addition to the David Sedaris library has hallmarks of his classics: the dysfunctional family values, the well-observed minutiae of human behaviour. Unlike in his classic tomes, however, the characters of this book aren’t human.

Following in the footsteps of Me Talk Pretty One Day and Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim, the latest addition to the David Sedaris library has hallmarks of his classics: the dysfunctional family values, the well-observed minutiae of human behaviour. Unlike in his classic tomes, however, the characters of this book aren’t human.

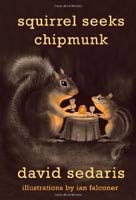

Squirrel Seeks Chipmunk is a collection of animal fables, absurd enough to remind you of Edward Lear and wise enough to evoke Aesop, especially when they have titles like “The Vigilant Rabbit” and “The Sick Rat and the Healthy Rat.” Where Aesop’s fables are cautionary or moral, those of Sedaris are rich comedic performances: satires of common human behaviour and rituals. He documents a slice of life in which mothers and fathers trade parenting tips in the schoolyard, but puts a spin on it by making those parents into chattering storks. He writes an hilarious dialogue between a housewife and her stylist, but the two women are actually a cat and a baboon. There’s something very pleasing about a society in which the skills and traits of a baboon will guarantee a career in the beauty industry.

There’s a certain kind of misanthropy in the stories and a whiff of nihilism: for all our pretenses as humans, are we not really a hoard of pooping, gossiping, socially-awkward, baby-producing animals? Like so many Richard Scarry characters, we are a mammalian society of naively evolved carbon-heads, muddling along and doing what we can. It’s not until you embed the common behaviors observed by Sedaris into his feathered and furry characters (sweetly illustrated by Ian Faulkner) that you get the anthropological distance required to make this observation without feeling weird.

Sedaris is known as an excellent public speaker (cutting his teeth at National Public Radio), so it feels appropriate to mention his excellent reading at the Librairie Paragraphe Bookstore in Montreal as part of his ongoing book tour. The hour-long reading added fantastic value to the book. In addition to a deadpan and adorably maudlin reading from the book’s titular tale (the sad story of sciuridae struggling to make dinner conversation and understand jazz), he read from a story excised from the final book on grounds of taste. It is called “The Shit- and Vomit-eating Flies” and depicts a conversation between a pair of foodie bluebottles: which parts of town have the most delicious vomit and feces. It’s a shame the story was cut from the book, but it made a very meaty bonus for those who made it to the event. He also read from a condensed work in progress: highlights from his personal tour diary, which will presumably be different depending on which leg of the tour you catch him. Continuing with the animal theme, one of these tour diary excerpts concerns a girl whose t-shirt had allegedly been “painted by a dolphin with scoliosis.” How and why a dolphin could be cajoled into painting a t-shirt boggles the mind. The detail of the scoliosis, much like the observational details salt-and-peppered throughout Squirrel Seeks Chipunk, can only further baffle and delight.