This was written for New Escapologist‘s now-defunct Patreon situation in 2020. It was the first of a show-and-tell series called Hypocrite Minimalist.

Object Number 1 in our inventory is a seashell.

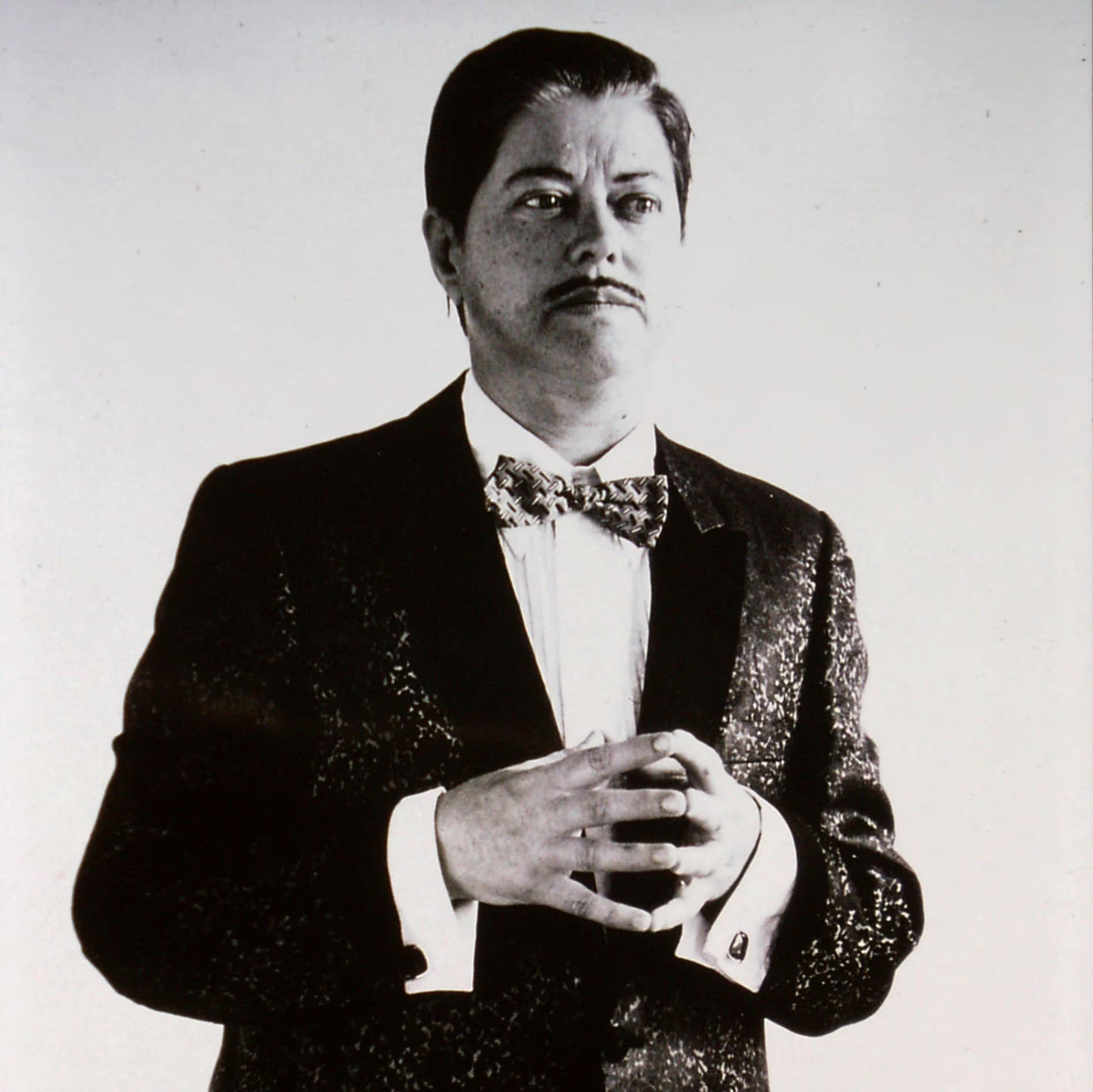

There’s a Glasgow writer and artist called Alasdair Gray. Well, there was, anyway. He died in December 2019. In life, he was the most famous writer in Scotland but was still (and is still) underrated.

His novel, Lanark, is considered remarkable by those who know it, but it’s not as widely read or adored as it should be. At the very least it should be considered a fantasy equal to Gormenghast, but really it should be more firmly ensconced in The Canon of Great Modern Literature. It’s a stunning book.

I became a devotee of his work in about 2004, hunting down and reading all of his harder-to-get novels and stories, visiting the places where his paintings or murals were purported to hang. I would not have fallen in love with Glasgow in the way I did were it not for Gray’s books.

Gray lived in Hillhead, one neighborhood away from mine, so I’d often see him shuffling around, usually on his way to the pub. I don’t think I ever took his easygoing presence for granted. Frankly, it always seemed miraculous that he was still alive: as well as being legendary, he was old, asthmatic, a boozer. I knew we were privileged to have him, that it was like being neighbours with Kurt Vonnegut or Angela Carter, a great cult author who’d always mean something to someone.

When he died, my photographer friend Alan was asked to photograph Gray’s flat before it was taken apart (he’d taken some shots of Gray himself at home earlier in the year). It was a rented flat and, while his sketchbooks and manuscripts would be looked after properly in an archive, the flat itself would not be preserved. I managed to attach myself to Alan so that I could go and have a look inside.

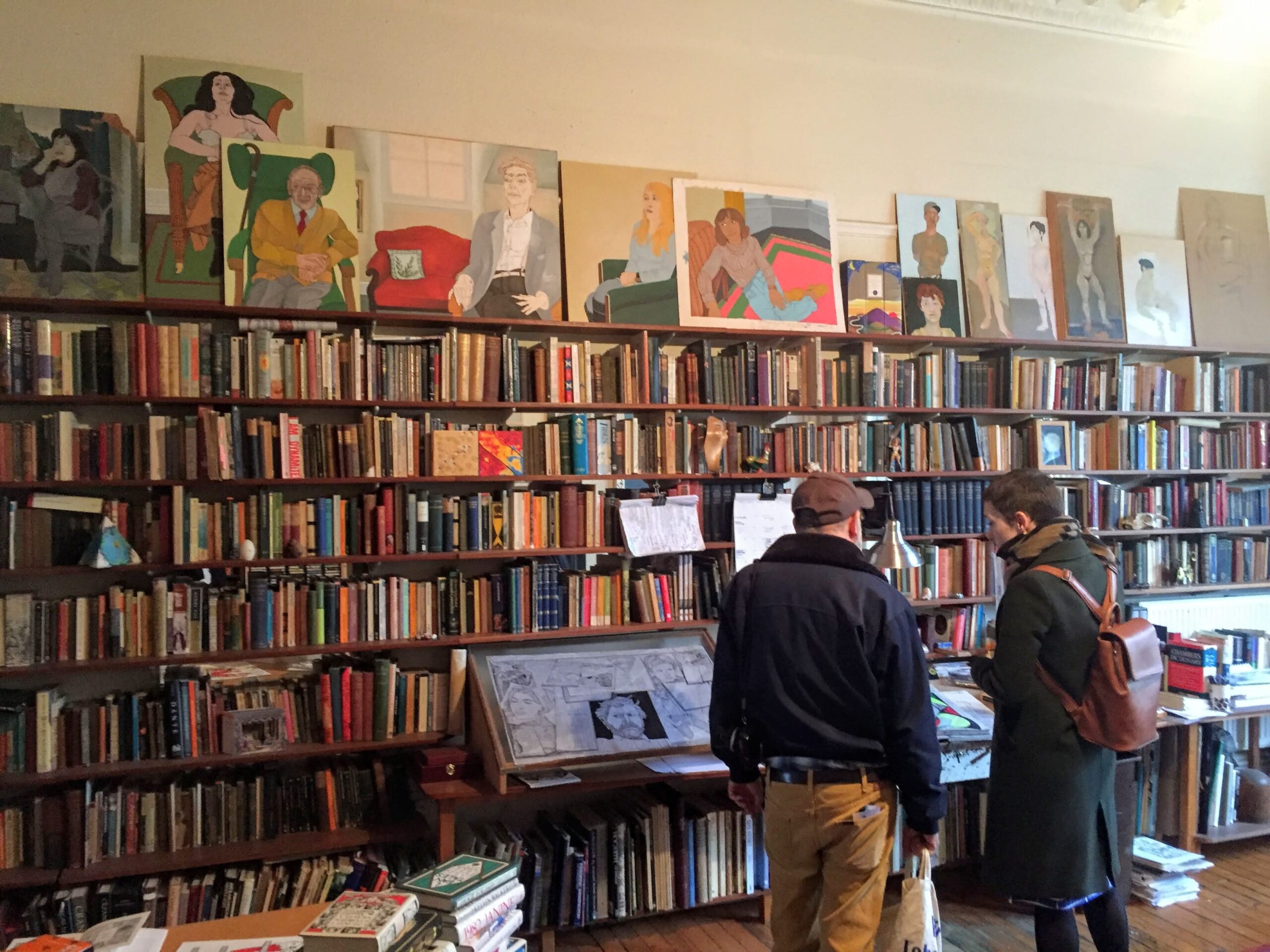

You can see loads of pictures of Gray’s flat by Googling, but here’s one I quietly took while visiting:

The place was packed with books and paintings and… souvenirs from nature. There were lots of little bones and stones and, yes, seashells. Apparently he’d bring them back from his walks on beaches. There are some seashells on top the heater in the picture above.

I did not steal the shell from Alasdair Gray’s flat, I hasten to tell you! I did not loot! No, while I was there, I made friends with Alasdair’s niece, Kat, who was clearly amused by my nervous, fanboy attitude to her uncle’s house. “I can’t believe I’m actually here,” I kept saying.

Gray’s flat, after all, is in the Lanark novel, when the protagonist walks through a hole in reality and meets his author. It was not this very flat, unfortunately, for the book was written when Gray lived a few streets further east, but the feeling was still uncanny. For just a little while, I felt like I was in Lanark. Well, I almost always feel like I’m in Lanark, actually, because there are so many recognisable Glasgow landmarks in the book, but by being in the flat I was in the very heart of Lanark. Sort of. In fact, one of the things I spotted was a metal trunk with the words “Lanark manuscripts” scrawled on it.

Anyway, blah-blah-blah. Get to the shell!

I met Kat for brunch a few weeks later. The efforts to box up her uncle’s archives was complete. And she’d brought me a memento: one of the seashells.

Gray had actually doodled on or inscribed some of the shells, but those were all destined for the archive and, I daresay, closer friends. But I have something from Alasdair Gray’s flat, for goodness sake. A talisman! A small but giddy treasure.

Here’s a picture Kat sent me of the shell before it was removed from the flat (next to another shell displaying Gray’s handwriting):

And here’s one last quiet photograph I took in the flat. The drafting table is where he worked:

*

Kat runs an Alasdair Gray website called A Gray Space. It includes, among other things, a virtual tour of the flat.

Here’s me and Kat, meeting for the first time in February 2020, in another pic taken by Alan.