Do you think piss freaks use this emoji? 💛

I think they probably do.

Do you think piss freaks use this emoji? 💛

I think they probably do.

Meat Cute.

Y-SO Negative.

I try not to be prejudiced against the posh, but there’s an article in Home & Garden magazine by someone called Tiggy Hatley-Dent.

Tiggy Hatley-Dent.

I mean, come on. It’s almost cruel.

“This emergency announcement is brought to you by… AirRaid.”

Happy Gray Day, one and all. To cocky chaps, wise old owls, urban foxes, queer fishes, merry devils, and back green puddocks.

Today’s the day chosen by Sorcha Dallas, his representative on Earth, to honour and remember the writer and artist Alasdair Gray.

Alasdair’s been gone five years now and I still miss him. I didn’t know him personally because I was too starstruck to introduce myself on any one of the countless times we passed on West End streets, but his physical presence was important to me. When I pass his old Hillhead flat, which I do all the time, I feel a sense of bereavement. I want to see his paint brushes on the windowsill, to know the wizard is in residence.

At 85 he was probably an old enough man to go: he’d had his fill of earthly pleasure despite being famously shy and he’d done more than his share of great work. But he gave to Glasgow an imaginary carapace, a glamour that lives on but, I fear, is dimming in his absence.

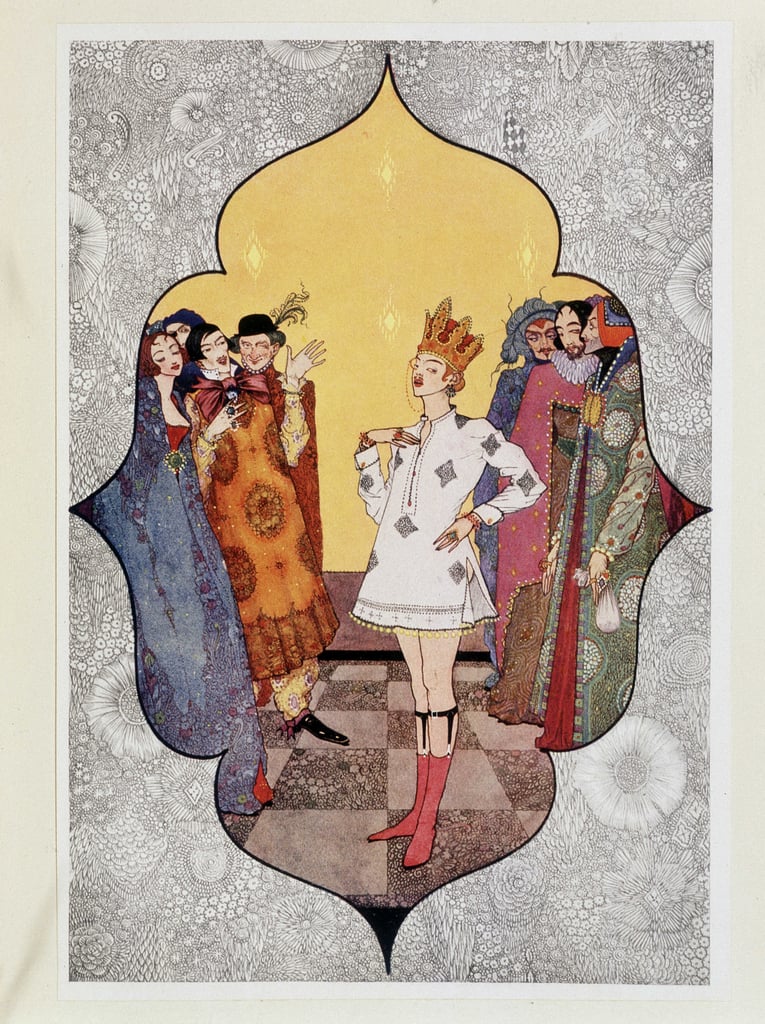

With Alasdair around, Glasgow didn’t look like a poorly-financed motorway city. It looked like this:

When his third-finest novel Poor Things was adapted for cinema by Yorgos Lanthimos and released early this year I was surprised to find myself frustrated that the London scenes in the film were not set in Glasgow as per the novel. I hadn’t expected to be troubled by this. Sorcha Dallas had written a generous statement about the film being something other than the book, that it could put forward its own vision of a world. I agreed. But as I sat in the Glasgow Film Theatre, supping from my plastic pint pot of Alloa ale, I changed my mind. Those scenes should have been set in Glasgow. For all intents and purposes, most of those scenes could have been Glasgow–Willem Dafoe had studied Gray’s accent and mannerisms after all and his housekeeper appeared to be Scottish too–but when Bella returns from her travels the word LONDON appears on the screen to make it good and clear. But why not elevate something (as Alasdair would have done, routinely positioning Glasgow as every bit as good as other European cities and his literary friends Agnes Owen and Edwin Morgan as equal to Jane Austen and Jonathan Swift) in your so-called art film instead of showing the usual images of a well-known capital now all but lost to oligarchs and Pret a Manger? Imagine how much more beautiful and intriguing those steampunkish rooftop vistas would have been had they consisted of the glotted spires, Grecian pillars, and Victorian mausolea of Glasgow instead of the usual metropolitan landmarks everyone’s seen a thousand times before. I think Alasdair would have preferred Poor Things to be set in Glasgow. But as I say, I never got to know him. I regret this.

Ah, never mind the film adaptations. His legacy is everywhere, in words and in pictures and in the deeds of the people he moved.

Here’s a reading I recorded for Sorcha a few years ago, on the first Gray Day. For my reading I chose a chapter of his undisputed best novel, Lanark.

It’s February 2024 and all is well.

Samara and I still live in Glasgow as the baby Jesus intended. I’m a writer. Never mind what she does, nosey.

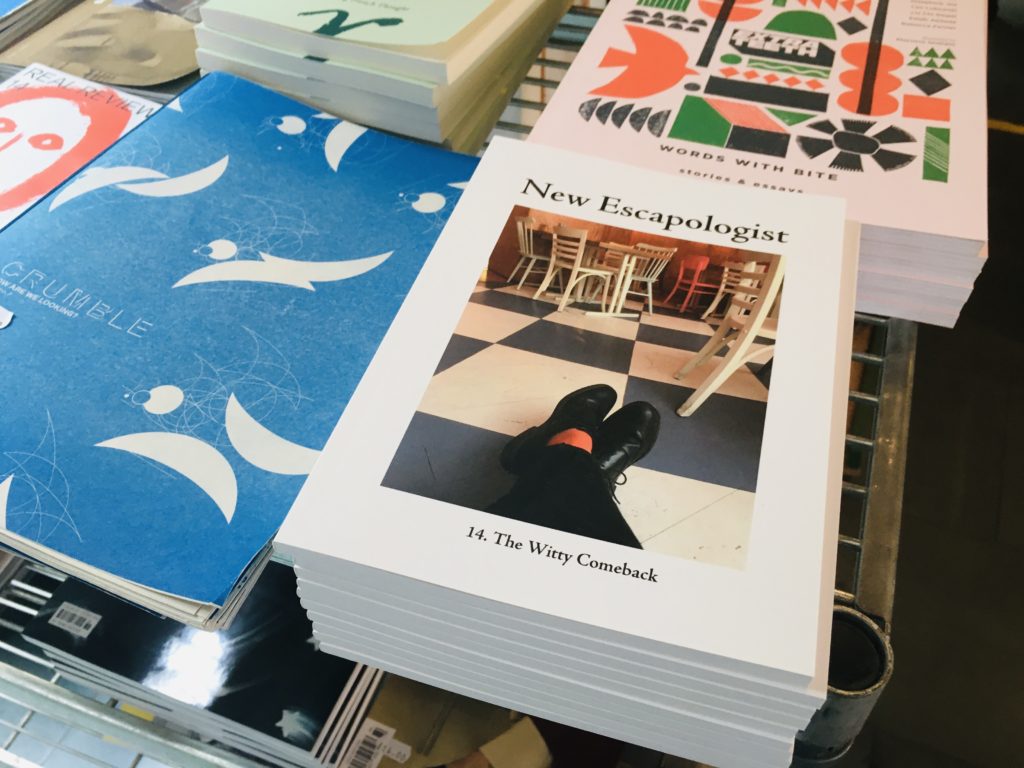

I run a small press magazine called New Escapologist. Issues 14 and 15 are sold out at the official website but we recently expanded into the real world with these cool shops.

I’m making a film with Mark Cartwright and Anthony Irvine about the Iceman. We’re basically turning my book into a documentary. I was down in Bournemouth this week, filming away.

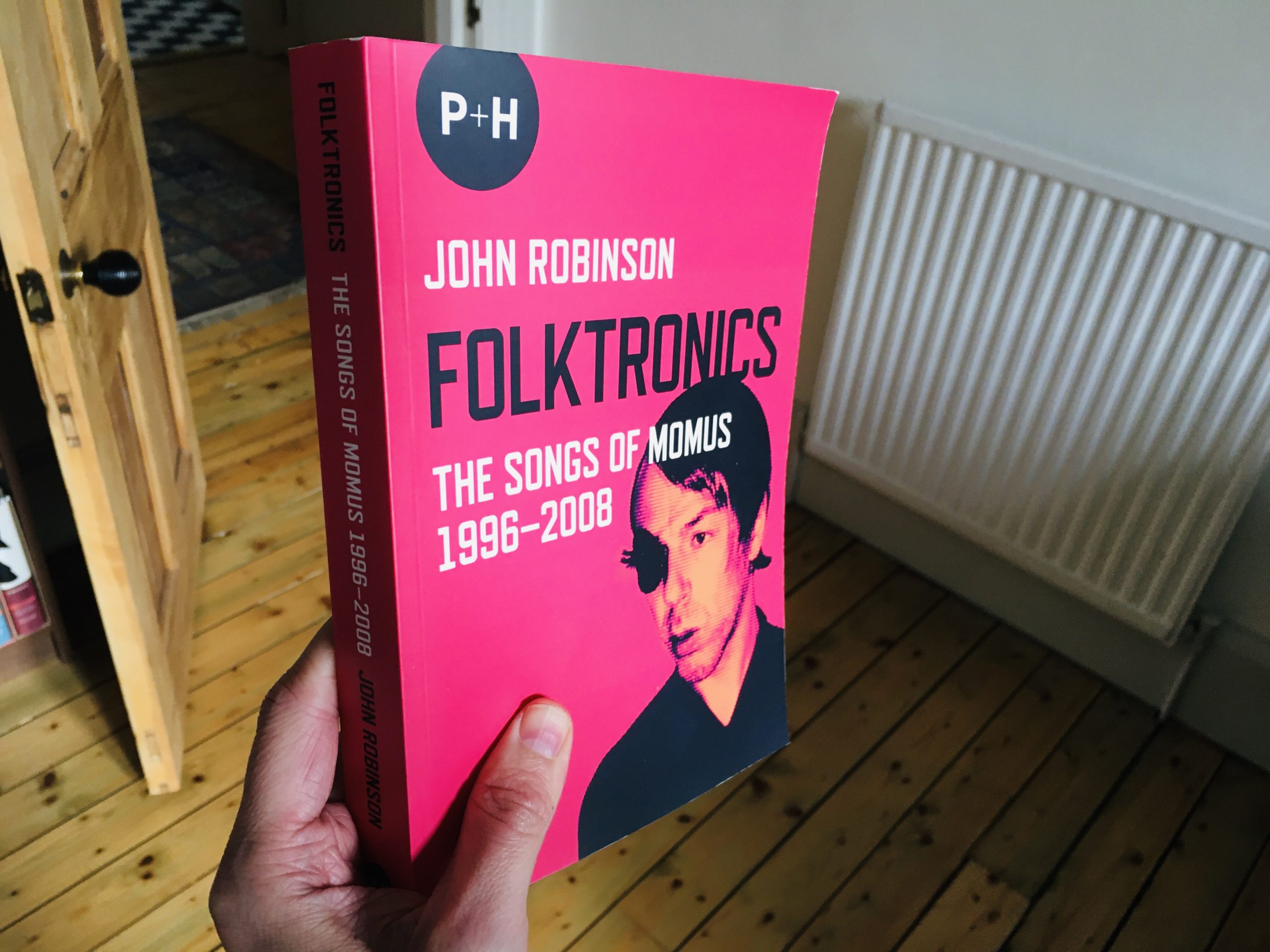

I’ve finished editing John Robinson’s second book about Momus. It was published this month and it’s a physically very beautiful book.

I’m writing a piece about my relationship with Richard Herring’s blog for the next issue of From the Sublime… magazine. The working title is “My Pet Man: 22 Years of Warming Up.”

I’m preparing for my live show in March. My posters are all over town, though the one at the Sparkle Horse pub keeps getting taken down and I keep putting it back up again.

I heard yesterday that I’m Out is being discontinued (all 1,300 remaining copies to be pulped) by Unbound who aren’t happy with sales despite their stupid cover and title change (that I advised against) and not lifting a finger to market it. I’ve got seven books under my belt now, but the stiff letter I sent to Unbound is one of the most satisfying things I’ve ever written.

I’m halfway through The Freewheeling John Dowie by, well, John Dowie. Dowie (I’ll stop saying Dowie in a minute) was a great alternative comic in the ’80s who quit the business when it became a business. He’s great. Stewart Lee mentioned him in the interview he gave us for the Iceman film a couple of weeks ago and I suddenly remembered “of course, I must read that book!” Unfortunately, it was published by Unbound (see above) who made an arse of things and is now out of print. You can buy it expensively second hand. Mine was free because it was damaged in the post and I demanded a refund. The book is at least brilliant: a grumpy memoir about cycling in Europe. It’s like Dervla Murphy but properly funny and realistically miserable. I love it so much.

I also recently read Werner Herzog’s excellently-titled memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All (which everyone should read but only if they’ve already read his more interesting Guide for the Perplexed) and Bonjour Tristesse by Françoise Sagan. The latter turned out to be translated by Heather Lloyd, my old friend Helen’s mum. I didn’t realise until I read her translator’s note and saw that it was signed off “Glasgow, 2013.” I enjoyed the unexpected sense of connection.

I was on the English south coast this week, filming with Mark Cartwright and Anthony Irvine and our little team. I’ve already said that. Pay attention.

We’re going to Lisbon next week. Like Lanark, all I need is some sunshine.

Most weeks, we attend a particular Monday night pub quiz. It’s a waste of time, money, and health but we continue to attend for reasons I can’t quite put my finger on. Maybe it’s because we keep WINNING. Oh yeah.

For TV, my partner and I have been watching old episodes of Jeopardy! after we enjoyed the recent UK version despite it being hosted by an awkward old taxidermied bear. On my own, I’ve been watching Inside Number 9, which I gave up around the fourth season but am enjoying catching up with. “Merrily Merrily” is my favourite story so far.

Some films I enjoyed recently were that Scala!! documentary, The Holdovers (which was so surprisingly good that I can’t stretch my imagination in a direction capable of criticising it – it’s a proper film like The Graduate or something, which I’m told is “mid budget”), and Poor Things (which was good but I found myself annoyed by the London bits not being set in Glasgow instead; why resist the call to elevate something instead of doing the same old expected shit?). I saw all of these films at the GFT. Support your local art cinemas, you sods.

Here’s my picture of the “month” so you can continue to monitor my ongoing decay, this time taken in Meadow Road Coffee, Glasgow, where I stopped to recaffeinate and to get a pebble out of my shoe:

Once Upon a Dog

A sitcom about fleas.

If I ever commit adultery, I’ll say to them “where have you been all my wife?”

Samara’s not so sure about that one.

My Glasgow show poster for Glasgow Comedy Festival is all over town and it looks great.

I especially like this one at the Super Barrio retrogaming joint in the City Centre. I’m squished in between posters for David Suchet and Jerry Sadowitz. What a lineup!

Meanwhile, in the venue itself (Drygate Brewery, East End) you can see my poster on this respectable notice board in the brasserie:

As well as upstairs by the bogs:

There’s a nice leaflet version here and there:

And this one is at the Sparkle Horse pub in the West End:

There’s also one in our kitchen, to scare myself when I’m getting a snack:

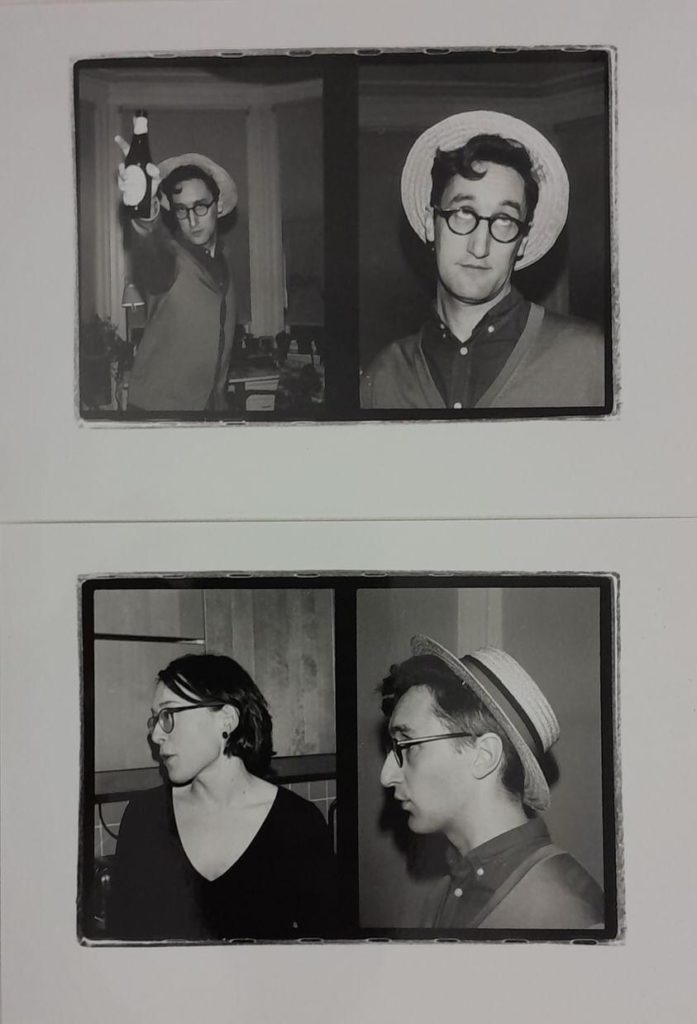

This photograph is from maybe 2018, sent to us just now by Alan.

Ever since mother snapped me from the side while horsing a Swiss roll, I’ve been a bit self-conscious of my nutcrackerish profile.

But look at it. Bottom right. I’m beautiful!

RIP, those glasses btw. The hat is Dimmick’s.

I got the Muppet Show theme lyrics wrong towards the end of that little essay.

I said, “It’s time to put on makeup, it’s time to light the lights!”

But the actual lyrics are:

It’s time to play the music, it’s time to light the lights.

and later:

It’s time to put on makeup, it’s time to dress up right.

So I conflated two verses.

I should correct it but I don’t wanna. The conflation suits my purposes.

What is the point in writing light or funny stuff when the world is so darn horrid? And not just funny stuff, why write anything? Or create anything? Or do anything not germane to The Struggle.

Well, here’s the thing. There’s always a struggle. We have two major wars raging right now, affecting everyone’s mood and sanity and the lives and deaths of thousands. We have the climate crisis. We have a cost of living crisis. We have a totalitarian attack on trans people and other increasingly at-threat minorities, the fallout of which impacts every last one of us, not merely the targets of the fascists’ ire. We have deep attacks on quality of life. Already the media eye has glumly moved on from the crises of Brexit and the Trump years, few of which are satisfactorily resolved and remain smouldering like that Springfield tyre fire. Permacrisis Naomi Klein and others have called it since last year. Or to quote what Stewart Lee believes is the first joke, “the poor will always be with us.” Jesus, the lad himself, was ordering one last fling to celebrate his pending crucifixion when a do-gooder apostle suggested they donate the shindig money instead to the poor. “The poor,” Jesus quipped, “will always be with us.” As well as being an early joke, it’s an early identification of permacrisis.

The trouble, as the King of Kings apparently had the foresight to know, of acting against permacrisis is that you’re always on the back foot. I salute the work of those in Greenpeace who go out in dinghies to jimmy the system. I applaud the work of angels who, also afloat, pluck refugees from the soup. I’m grateful for those in Israel who devote their privilege to the tireless campaign for peace and an end to the madness. They’re doing what they have to do and they’re doing the right thing. They’re heroes. But they’re also in a state of unending triage. They’re a kind of casualty themselves. Imagine what those people could do if there was no malevolent pollutant to protest, no desperate to save, no bombs and rape in the war zone. Imagine what could be done with that energy and goodwill and brainpower in a time of lasting peace. Imagine what could be done if, instead of having to take out the Space Invaders one by one, we could find a space behind one of those oh-so-fragile little bunkers to create. Imagine what we could do if those noble jimmiers and campaigners and rescuers could afford to be on the front foot instead of the back. Think of the pleasures they could enjoy for themselves and create for others. Think of what they might build.

“But I get tremendous satisfaction from my job as a nurse,” you might protest. Yes, yes. And I’m grateful. Thank you, thank you, thank you. But I don’t think you’re saying that viruses and injury and abuse and infirmity are good things because they allow you to Do Good. Are you? Of course you’re not. I’m just asking that we don’t stop thinking of a world beyond chaos and death and hunger. And that we–some of us, those who are free and able to do so–get on with making that world.

When I see injustice, I’m always tempted to write about it. That’s honestly my first instinct. I want to write a column, fire off a tweet, write a letter to my MP. The idea is to appeal for sanity in the world, to join the chorus instead of vanish into silence, to help prevent further mistakes, to draw attention to systemic injustice instead of personal vendetta. Sometimes the lure is so hard to resist that I actually do these things. But imagine if I didn’t have to. Imagine if I could put that mental energy and time and finger wrigglings into writing a novel instead or a funny column or a sitcom or a film. Something of less consequence. Something about nothing. That’s what we should all be free to do. The world would be better off for it, not in the “we stopped a bad thing” way but in a “we created a good thing” way. The real victory in Europe wasn’t in wrestling Germany to its knees but in creating the post-War welfare state and the wave of midcentury art that would result from it all. This should be the aim of any socialism: not to pick up after totalitarianism or capitalism or even to stop them per se, but to create and live out the alternatives in real time. It should also be the aim of any society: not to wage exhausting battle with our idiot governments but to build the alternatives, right now, in the streets, in the fields, in workshops, in homes, in art, in people.

At the risk of sounding paranoid, I suspect (though I do not know) that our leaders are aware of this. While we’re picking up after their corrupt and incompetent mess making, we’re not doing anything outrageous that might lead to–or, better, is an example of–true emancipation. When we’re not making art–a good thing to do inherently but also in terms of exponential increase of joy it can bring in the long term–we’re not a problem to them. It’s better in their view to keep us struggling, better to keep us grappling with impossible paperwork and asking for medicine for a third time and demanding that the libraries we paid for aren’t shuttered and closed. While we’re talking about Brexit, we’re not campaigning for socialism. (Brexit killed Corbyn. Admittedly, it killed a bunch of their guys too, but they have veritable factories devoted to the production their guys while we only had the ball for a brief and shining moment.) And we’re not beautifying our world instead of working for them.

So that’s what permacrisis is. Or at least what it has done. Whether by design or by happenstance, it has gubbed up the channels. It has a way of making sure We The People never accomplish anything worthwhile. It’s all about the back foot.

The only way to combat this–in my opinion and don’t mind me–is to stay on the front foot for as long as you can. Instead of despairing and reducing your lot in life to picking up after the malevolent cretins in industry and in our governments (now practically one and the same) by dwelling on what seems immediately “relevant,” create art. Create, if you must, through despair and guilt and shellshock, art that strikes at the heart of these crises. But the greatest thing to do (IMHO!) is to create art that is nothing to do with crisis at all.

Create witty, funny, joyful, pretty, beautiful, happy art. Instead of reacting eternally to the Bad, push onwards into the Good. So few people are doing it, fewer still with the knowledge of its importance. Push on, on, on. Wear bright colours in times of darkness. Make sweet music, paint the ceiling. Truly, it’s time to put on makeup, it’s time to light the lights. To create something other than a response to crisis is not to support crisis or to ignore it. There’s no contradiction in hating the Bad while putting your energy into creating the Good. Why piss around with pawns and defence when you can get your bishops and knights out into the endgame? The endgame, it’s easy to forget, is a world of peace and freedom and flourishing. Make it.

I often find myself thinking of Martin Soan. I think of him when I hear the phrase “my giddy aunt” or see some meerkats in a zoo.

Most often though, I think of him when I clean the gunk out of the hair trap in our shower drain.

Martin has a bit where he comes on stage to Serge Gainsbourg’s Je t’aime, while “erotically” tugging some grotty-looking wool out of a section of drain pipe.

The music scratches to a halt and he says “Cor, I love doing that.”

I probably think of that every single morning.

December 2023 is almost over and I should be thinking about my end-of-year roundup more than updating the Now page. What can I say? I live in the Now.

My partner and I still live in Glasgow, Scotland. I’m a writer, though much of my work these past few months have been writing-adjacent or administering the necessary business side of writing. I’m fine with that.

From the Sublime… just published a piece I wrote about Pogs and nostalgia in their second issue. It was fun to write about the idiotic cardboard discs and I like the whip-pan “Dudley via Honolulu” structure I came up with.

I’m making a film with Mark Cartwright and Anthony Irvine about the Iceman. We’re basically adapting my book into a documentary. It’s been nothing but fun so far. We’re trying to cover some of our expenses with a Kickstarter so please chip in if you can.

Issue 15 of New Escapologist is out now. It’s been my main workload for at least two months: writing, commissioning, editing, proofing, printing, promotion, shipping. I’m trying to arrange proper distribution for this one too, which I think will happen in January thanks to distributor Ra & Olly.

My first novel, Rub-A-Dub-Dub just scooped a Saltire Award for Best Book Cover. Amazing. September also saw a nice interview about the book with my old friend Reggie Chamberlain-King in Pop Matters.

I’ve almost finished editing John Robinson’s second book about Momus. It’ll be published by P&H in February.

This is a lot of work for me. I’ve loved every minute of it but I’m looking forward to a proper break while the world enjoys Christmas and probably a deceleration in the year of the orangutan.

I’m currently reading Bore Hole, the memoir of Joe Melen who drilled a hole in his own head. Recommended.

I also recently read Butts by Heather Radke, a cultural history of arses.

Nina Simon’s Gum by Warren Ellis, meanwhile, is the story of how the Dirty fiddler pocketed Dr. Simone’s gobbed-up gum at a concert and what happened next. It’s fab.

My partner was finally granted citizenship this month. Rejoice! It’s been a long journey. Her passport also arrived today (a separate process, by the way), which means we can leave the UK for periods longer than 180 days if we want to. Ironically, citizenship means the ability to stay without fear of deportation but also the ability to get off this blasted island.

I was in Paris recently, visiting the Asia Now exhibition, dossing in a hostel, and hanging out with Landis who was over from Chicago, signing books and consorting with publishers.

I visited the Netherlands in November ostensibly for a day of Le Guess Who? festival in Utrecht but also flaneuring around (and hostelling again) in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Delft. Oh! And Luxembourg, which isn’t even in the Netherlands! It’s hard to convey how much I enjoyed this trip: the freedom of solo travel, all those lovely European trains, a rich variety of experience.

I was filming in Wolverhampton and Birmingham later in the same month with Anthony and Mark, and also meeting the amazing Fliss, Jim, Michael and Arthur.

Most weeks, we attend a particular Monday night pub quiz. It’s a waste of time, money, and health but we continue to attend for reasons I can’t quite put my finger on. Maybe it’s because we keep WINNING. Oh yeah.

For TV, my partner and I have been watching Moonlighting (1985-89), which is a lot of fun so far with its fast-talking silliness and two charismatic leads but I worry about all the fourth-wall breaking that’s starting to happen in the second season. On my own, I’ve been watching Season 5 of Fargo, which is awesome. The pared-down minimalist narrative doesn’t get my blood up like Seasons 1-3 but is a welcome reduction after the messy Chris Rock season.

A film I enjoyed recently was Other Music, a documentary about the important record shop in New York City. I also enjoyed Wil Hodgson’s comedy show Barbicidal Tendencies, free to watch on YouTube thanks to GFS.

Here’s my picture of the “month” (this time with Mark and Anthony) so you can continue to monitor my ongoing decay:

You’ve already seen that one? Okay, here’s another:

Coming home from a trip to the impossibly well-organised and lovely Netherlands, I’m immediately irritated by everything I see in the UK.

Seeking out the correct bus stop at the airport, a man in a high-vis gilet is standing in front of the time tables. “Can I help you sir?”

“Home to Glasgow,” I say, “I just want to know the time.”

He checks his watch and tells me the time.

“No,” I say, “the time the bus arrives.”

He moves aside and jabs at a filthy laminated notice. “55 and 25 past the hour.”

“Thanks,” I say, though all he’d done was get in the way of this information.

There’s ten minutes to wait, so I nip into the M&S for a sandwich. There are no self-service machines so I stand behind an older woman talking to the only server. She’s taking ages because buying a sandwich with a contactless card in an airport terminal requires plenty of chat. Another server walks purposely to a second cash desk, looks directly at me and nods. I go up to her and she says “I can’t serve you at this one because blah-blah-bloopty-bloop” so I turn on my heels and rejoin the “queue,” mindful of the time. She eventually calls me to a third cash desk. She can tell I’m irritated and we conduct the transaction in silence until I break it with a “thank you” she doesn’t respond to.

I eat my sandwich while waiting for the bus but have to leave the queue to bin the packaging. Why is there no bin near to the stance?

A sign at the stance says almost boastfully that the journey will cost £13, which seems expensive. For £24 this week, I travelled by rail for six hours and crossed three international borders from Rotterdam to Luxembourg.

I board, pay, sit and watch the other passengers, many of them tourists or new arrivals, boarding. A young Black guy comes along with his small wheeled case and his phone out.

“Come forward with the bag sir,” says the gilet officiously, indicating the luggage hold. “Put the phone down and bring the luggage forward.”

Put the phone down? I’d have shoved it up his arse. Gammon fuck.

The passenger politely asks about the ticket on his phone. “Ask the driver,” says the gilet, hefting the luggage into the hold even though the passenger doesn’t yet know if his ticket’s good for this bus.

The next passenger is a white Scottish woman who has a ticket, she says, for the Megabus (which isn’t this service and could have cost as little as £4) and the driver lets her board.

A digital screen in front of me reads “please take care on the stairs.” But anyone who can read the message has already passed the stairs.

I glance at the receipt the driver gave me and it says “£14.80,” even more than advertised.

We cruise home through the rain, the driver simultaneously playing loud local pop radio and whistling. Not to the melody but to the lyrics.

Anyone got an EU residency permit they’re not using?

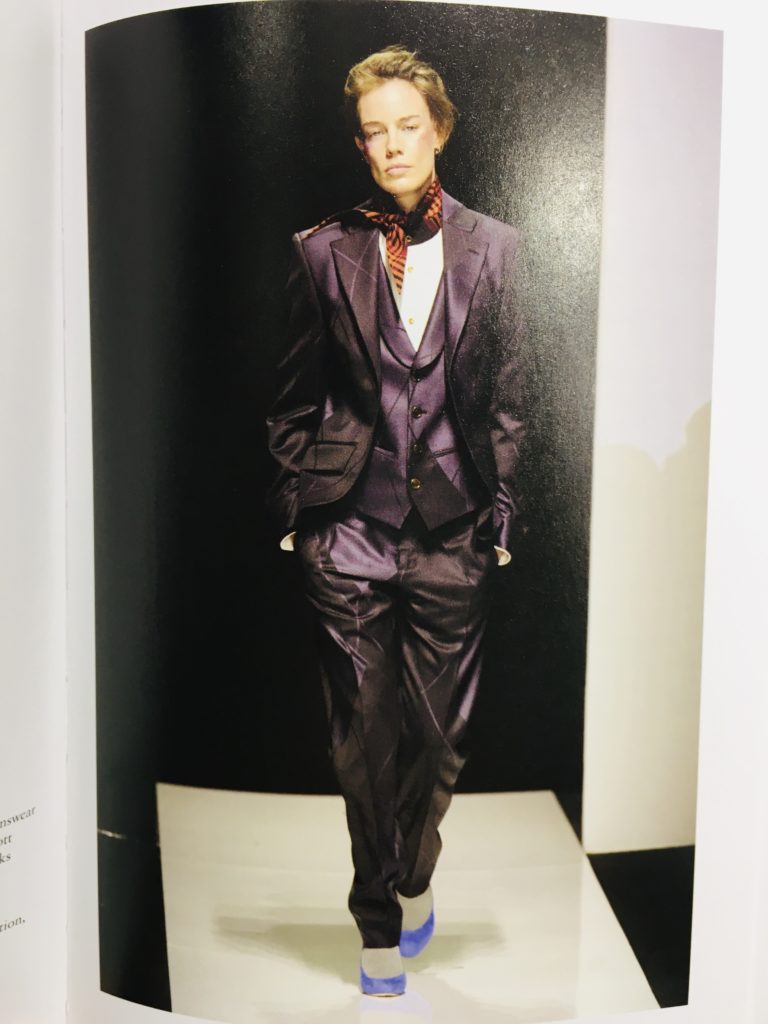

I’m doing some filming on the weekend for a documentary and I’m trying to decide what to wear.

I want to look good for it but it’s important not to steal the scene. Here’s some inspiration:

Look! I finally got a review for my novel! From Goodreads.

Funny it ain’t. Or, at least it’s not my idea of funny. I don’t find indignities of waged labor or alcoholic overweight body or borderline psychotic in any way humorous. What somewhat redeemed the novel for me are references to other books, the books Mister Bob reads and some fine literature is that. Additional half-star is for the mention of French phenomenology. However, the novel could’ve done much better with it, especially in regards to the body, instead of unstably jiggling on the edge of farcical. Such as it is, I barely see the point of it all.

If that’s whet your appetite, Rub-A-Dub-Dub is available in paperback and digital formats from P&H Books.

September 2023 is breathing provocatively down our necks. My partner and I still live in Glasgow, Scotland. And I’m still, thank fuck, a writer.

Autumn is approaching and I’ve been eating veggies and apples from Alan‘s allotment. Nature’s bounty has NOT given me the squits. In banal news we’ve got a new sofa bed coming tomorrow. We sold the old sofa on Gumtree last week and we’ve been sitting on the floor ever since.

Last month’s Kickstarter to bring back New Escapologist went extremely well. In fact, it outstripped all of my expectations. The first new issue of the magazine is now printed and available and continuing to sell well.

Work has already begun on Issue 15. I’ve been writing, editing, and commissioning like a trooper.

The magazine is available in a handful of shops as of this month too. The ever-supportive Aye-Aye Books in Glasgow has a hefty wodge of copies, while Print Culture and Good Press in Glasgow are stocking it too. Exciting news for Londoners: we’re also stocked in the famous magCulture now. Success!

Also this month I’ve been working hard to promote my first novel, Rub-A-Dub-Dub. This has involved interviews and prize submissions and some chats with booksellers. I’m not sure when this will all start to pay off.

Oh! And I had a piece about the Iceman published in From the Sublime…, the cool new zine from Manchester.

I’m currently reading Salinger’s Nine Stories. This particular copy was given to me by Martin who found it in a Montreal bin.

I also recently read Claire Dederer’s excellent Monsters, Rodge Glass’s biography of Alasdair Gray, John Robinson’s first of three biographies of Momus (which I enjoyed so much that I uncharacteristically left a review for it at Waterstones), a so-so selection of comic essays by Sloane Crosley called I Was Told There’d Be Cake, and a great comic book called Hell Phone by Benji Nate.

We’re still waiting on my partner’s citizenship application and trying not to think about it.

This month I was in Wolverhampton to be interviewed for YouTube by Ginger Beard Mark, Hay-on-Wye to see some middlebrow tourist bookshops, and at the Edinburgh Fringe for fun and profit.

I’ll return to Edinburgh this week for some exiting hangouts and to see Simon Munnery’s Fringe show, Jerusalem.

Most weeks, we attend a particular Monday night pub quiz. It’s a waste of time, money, and health but we continue to attend for reasons I can’t quite put my finger on. Maybe it’s because we keep WINNING. Oh yeah.

For TV, I’ve been watching Fleishman is in Trouble, which is okay but I don’t particularly recommend it. Danes dains to be great in it. My partner also got us into Gothic Homemaking with Aurelio Voltaire, which is exactly as it sounds.

The main film I can remember watching this month was The Red Shoes, a beautiful 1948 Powell and Pressburger movie. Oh, and Barbie at the GFT, which is a load of old piss really but the atmosphere in the cinema was fun.

Here’s my picture of the month (this time with GBM) so you can continue to monitor my ongoing decay:

Two questions concerning the narrative voice in Rub-A-Dub-Dub.

The first comes from Reggie Chamberlain-King in an interview (yet to be published) we did together. He asks:

I was interested in the perspective of the narrator. It’s a close third person perspective – not omnipresent, more reporting from Mister Bob’s shoulder; judgmental, insulting, but ultimately sympathetic. What is the relationship between Mister Bob and the narrator?

Thank you for saying that. That’s literally how I envision the narrator: a glowing orb just above and behind his shoulder. This narrator has access to his thoughts and personality as well as what the character sees, so she/he/it can report both. I suppose that’s omnipresence really but some of Mister Bob’s personality is in the narrator too. They’re conjoined. I like that very much but I think it confuses some people, which isn’t something I wanted to do. Some said it was too close to him, especially when it sounded judgemental of him: “Mister Bob was fat. And he had gingivitis.” Lines like that are supposed to be second-hand thoughts originating with Mister Bob but reported by the narrator. I don’t think this idea for a narrative voice is iconoclastic; I’m certain I’ve read this sort of voice before. But it’s good that it’s catching people’s interest.

The second question comes by email from reader Scott:

I’m well into Rub-A-Dub-Dub. Just finished Part Three. I loved Mister Bob standing up to Mrs. Cuntapples! Tell me about your voice for this novel. I know you pretty well by now and this is not the Robert Wringham I thought I knew. Very short, repetitive sentences. For example you said “premium strength lager” many, many times and no doubt on purpose. Why not beer, brew, or even bottom-fermented grains? You must have had a reason. And “Mister Bob” is literally uncountable. Why not a pronoun or two? Please let me know as I’m thoroughly enjoying your first novel but trying to unlock the idiosyncratic writing style.

The Robert Wringham name is on the cover but the narrator is not Robert Wringham, so it’s a different voice to anything you’ve read of mine before. The repetition is indeed deliberate and for two main reasons.

The first is that the narrator mocks Mister Bob and his gritty predicaments with an almost sing-song or storybook tone: “Mister Bob fell in a hole. Oh dear,” etc. It’s supposed to offer a sort of juxtaposition or tortuous understatement that makes light of the post-Brexit, pre-pandemic UK hellscape in which he has found himself, a world where systems seem to be winding down and ceasing to work smoothly.

The second reason is an investigation into quiddity: certain things in a repetitive or cyclical life gain thingness as we go around and around. A fire hydrant we see every day becomes not a fire hydrant but the fire hydrant. I applied this theory to significant objects in Mister Bob’s world: the premium strength lager, the polyether railway company uniform, the buffet car, David McManaman’s “head in the shape of a triangle,” the word “reek,” certain placenames. There are others. The phrasing is always the same because his (and, increasingly, our) familiarity with those objects is at optimal thingness, no further familiarity could possibly be layered onto them.

This is the level of thought that has gone into my novel, people! It’s intended to look lightweight and silly but the engineering beneath the page is secretly significant.

*

Rub-A-Dub-Dub is my first novel. Here’s where you can get it in print or as a digital download.

I dropped off some fresh book stock off at Aye-Aye Books, the indie bookshop at Glasgow’s CCA, this week.

They look great on the shelves. But don’t let that put you off buying them.

It’s July 2023. My partner and I live in Glasgow, Scotland. I’m a writer.

It’s summer and the sun has been shining. I have a big pile of library books to enjoy. We recently made the switch from crap vegan margarine to real butter from a dairy I used to walk past when employed by Stirling University in 2014: it gives me a pleasant sense of connectedness when I spread it on my toast.

I’m bringing back my small press magazine, New Escapologist and I’ve been working joyfully on the comeback issue. Please back the mag’s return on Kickstarter if you’d like to.

I published my first novel earlier this month. It’s called Rub-A-Dub-Dub.

Go Faster Stripe recently published my book Melt It! (with Anthony Irvine). We had a launch event of sorts at Guggleton Farm Arts in England last week.

I’ve been reading about early German Romanticism, fungi, Dora Carrington, and Eric Gill. I love public libraries.

I just got my passport renewed! It took only two weeks.

This month we’re also applying for my partner’s UK citizenship. Wish us luck please.

I spent last week in London, Devon, and Wiltshire. There are photographs in the July section of my Tumblr photoblog.

Most weeks, we attend a particular Monday night pub quiz. It’s a waste of time, money, and health but we continue to attend for reasons I can’t quite put my finger on.

For TV, I’ve been watching Jeopardy! Masters, Mr. Inbetween, Cobra Kai, The Bear, and Avatar: The Last Airbender.

The only film I can remember seeing this month was The Red Shoes, the devastatingly gorgeous 1948 Powell and Pressburger film.

A friend sometimes gives me free tickets to the GFT. The most recent film I saw was Beau is Afraid. It gave me a nightmare.

I’m in London for the week and having a great time. It’s busy though and there are always moments in this city when I feel like a rube.

Shortly after arriving at Euston, a woman approached me on the street. I’m good at letting people down when they’re asking for money by giving them a friendly smile and a “sorry” but there was something a bit different about this person’s energy.

“I am French,” she explained, “No one believes me but my wallet has been stolen.”

She was holding her handbag open as if to reveal no wallet.

Looking back, I think she was probably a scammer but I half-believed her at the time and I still worry that I failed to help someone who was in a rare pickle.

She didn’t look like the typical scammer. I think she really was French and, while the bulging Marty Feldman eyes made her look slightly odd, she seemed to be middle-class and uncomfortable about asking for help.

“What do you need?” I asked, thinking I could perhaps call someone for her.

“Six pounds,” she said, for a train back to somewhere.

“I don’t carry cash,” I said truthfully, “maybe if you go back to the station and speak to the ticket sellers they might be able to help you,” and I walked away.

When I peeked back, she wasn’t flicking me the V’s or routinely hassling a next person; in fact she seemed a bit deflated. It was true that I had no cash but I suppose I could have gone to a cash machine if I only had been more certain she was for real.

I’m 50-60% sure it was a scam and I’m sure some of you worldly Londoners will confirm if this is a common wheeze, but she seemed more plausible than our Glasgow scammers and I worry that I sent a nice woman back to the continent angry about her time on Brexit Island. She’d been mugged and then not helped by anyone. You know, unless this was all a bollocks.