Originally published in the Winter 2024 edition of Etrog.

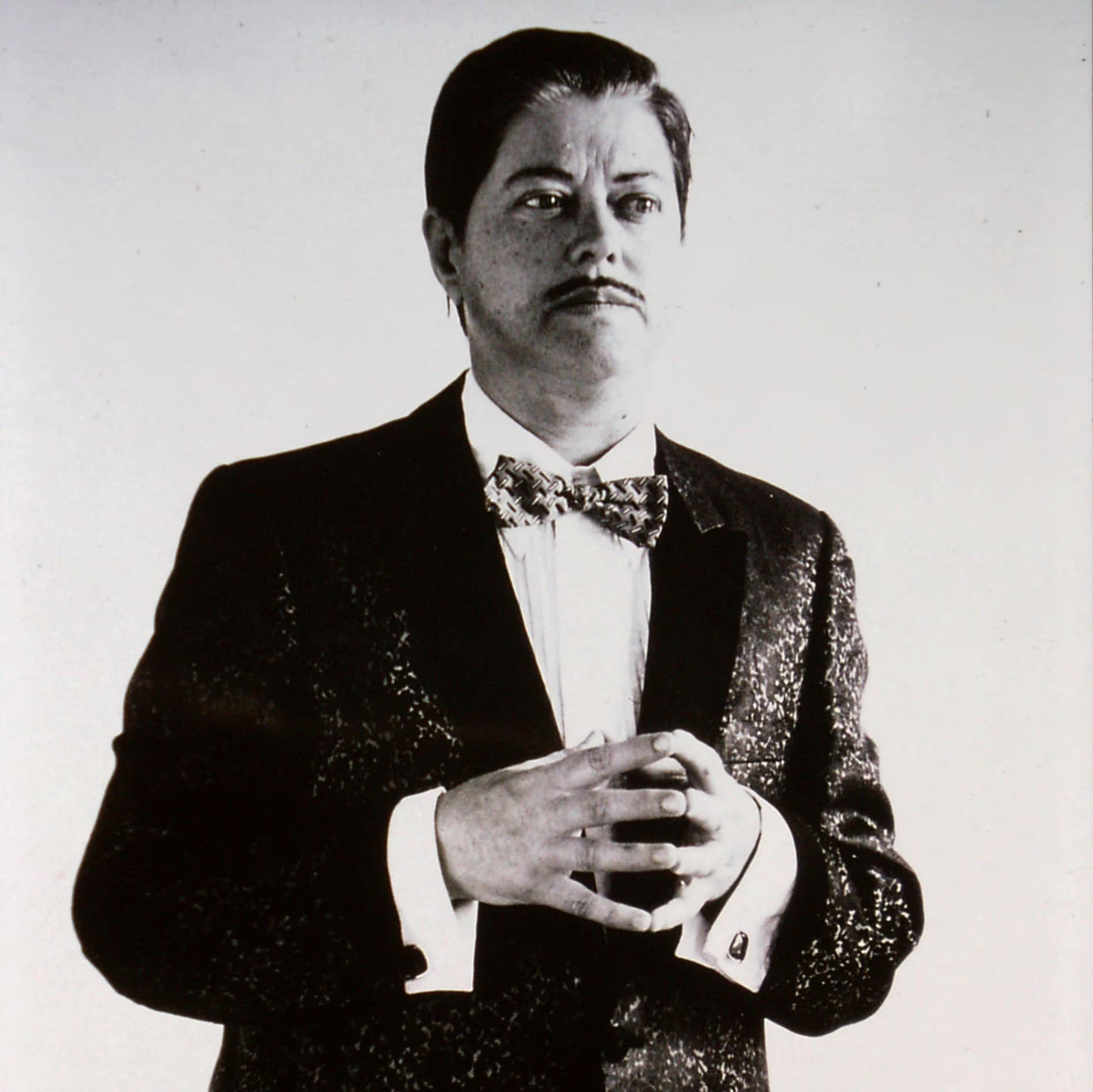

Ivor Dembina is touring a show called Millwall Jew. It’s about about his support for Millwall FC in the context of Jewish Londoners traditionally siding with Tottenham.

That’s probably a real rib-tickler if you like football. Fortunately for softies like me, Ivor brought an additional show to the Fringe this year called Nineteen Ninety-Four, a celebration of his 40 years of schlepping up to Edinburgh with little but a suitcase and a mouthful of zingers.

As I approached the venue, the Dragonfly, I spotted Ivor flyering outside. Always a good sign.

“Hello Ivor Dembina,” I said, “I was just coming to see you.”

“Then that places you in an elite crowd,” said the stalwart, “you’re my only ticket.”

40 years, folks. That’s showbiz.

Despite moving in adjacent and overlapping circles for 20 years, I’d never really met Ivor before. We once said hello at a Political Animal midnight show circa 2008, but we were both blind drunk. Blind enough in my case to be trying to chat up Andy Zaltzman. Then, this July, we both played South London’s PEN Theatre on the same weekend and would have shared a dressing room if only he’d not been doing the Saturday and I the Sunday. I was 24 hours too late, which, curiously enough, is precisely how long it takes to get some of his cleverer jokes. No wonder people were laughing so much.

“Give me some of those,” I said, and started handing out flyers, all time-honoured like.

It was getting on to 4:30 in the afternoon and the people trudging past were all wage slaves, escaping West Port with a sly half hour in the bag. It’s about the little victories with some people, which wasn’t much use to those of us in the Ivor Dembina business.

I stuck flyer after flyer under their noses, but each commuter was determined to push on Waverleywards. The most generous of their number made a sort-of “bleurgh” noise in acknowledgement of, one assumes, our common humanity. It’s terrible what’s been done to them really; they can never know the bracing freedom of the jobbing comedian. Or be bothered to help alleviate our bracing poverty.

“Well then,” said Ivor after a few minutes of drive-by rejection, “I’m going inside,” leaving me, armed with some leaflets and my wit, to drum up a crowd. I’m not sure why. It’s never worked before.

A couple stopped to talk to me. No office workers, this pair. Salt of the Lanarkshire Earth. “Who is he?” said the one with the NSFW tattoos.

“He’s Ivor Dembina,” I said, affecting a note of the flabberghast, “a legend of the fringe. 73. He won’t be coming up forever, you know. Catch him while you can?”

Unbelievably this worked and soon we, the audience, went inside to take our seats.

“Look,” said Ivor to the four of us (hey, it had threatened to be an audience of one), “this isn’t as many as I normally get in. Shall we see how it goes? We don’t need to do the full hour.”

“Get on with it!” someone shouted. Though I say it myself, we were a good audience.

But we were also a strange audience. There was me in my winklepickers, Mr. and Mrs. Lanarkshire 1962, and a depressed young man whose one-person play, he said, was being done a disservice by the stinker he’d cast in it. Ah, the Fringe.

The show was great. Ivor did his an-oldie-but-a-goodie jokes about his life as a Jew, delivering them not at the front of the room like some run-of-the-mill comic, but while striding around, weaving in between us, which had the effect of making the room seem fuller than it was. Now, that’s a gift.

“So I was walking down the road, as the comedians say…” said the comedian.

“Which road?” I asked. Technically this was a heckle, but he’d been doing so much crowd work that he could hardly fall back on “look mate, this isn’t a collaboration.”

“The Holloway Road,” he said, “Joins up with the A1.”

“Glad I asked,” I said.

“Good heckle,” he said, “You’ve earned a pound.”

Later, he asked us what a Jewish equivalent of Playboy magazine would be called.

“Playmensch,” I suggested.

“No,” said Dembina, “not that…”

“Playgoy?”

“That’s it. 50p.”

The spirit of the Tunnel Club is alive in Edinburgh.

As the audience filed out as “en masse” as four people can realistically manage, Mr. Lanarkshire stopped to say something unsavory about Palestine.

Well folks, Ivor and I have 60 years of comedy chops between us, which qualified us to marshall our not-inconsiderable wits and to say in unison: “oh fuck off!”

As retorts go, it’s a classic really. Try it yourself.

🍋

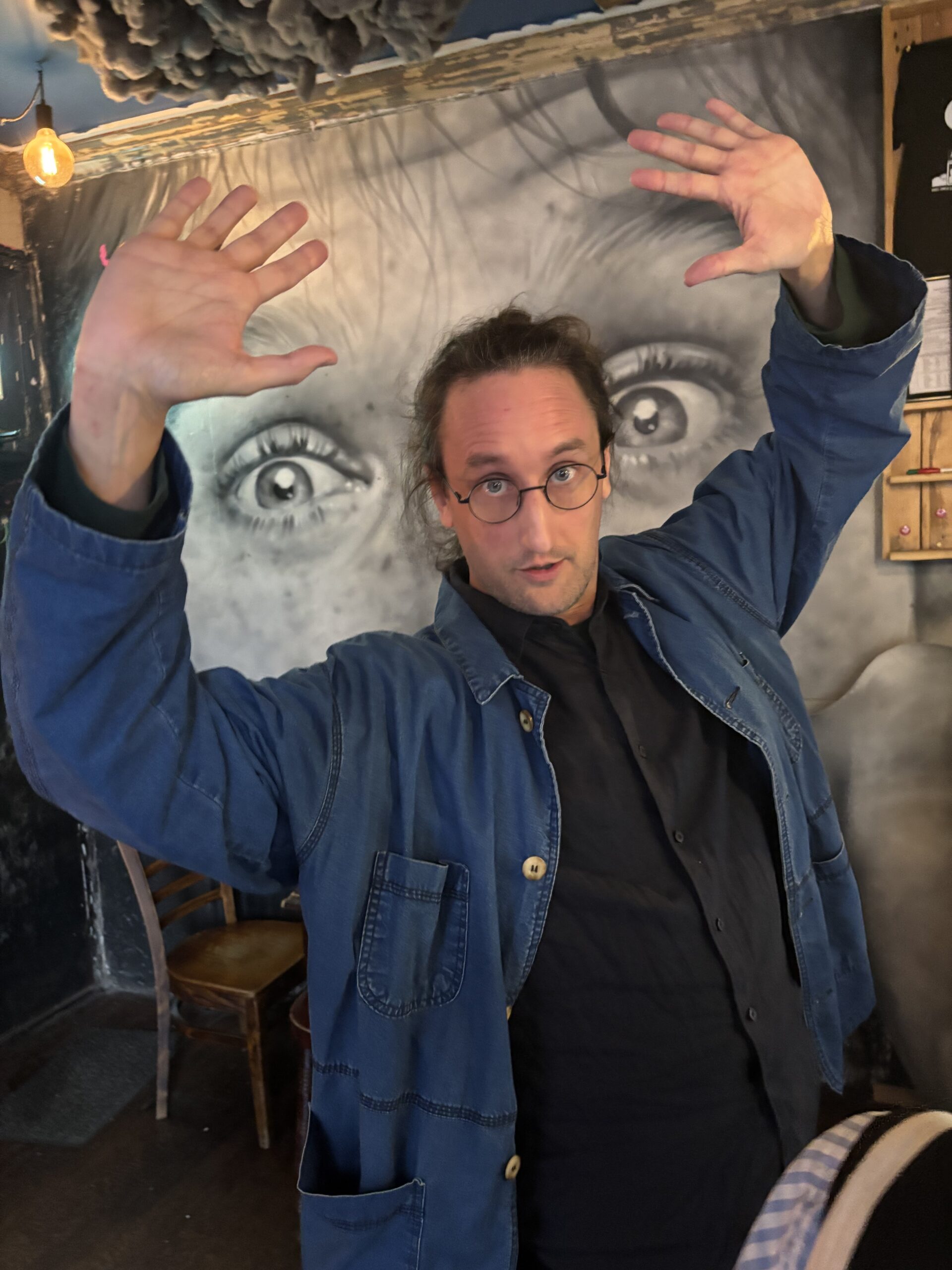

If this resonated with you, (a) shame on you, and (b) please consider buying my books A Loose Egg and Stern Plastic Owl or reading my blog at www.wringham.co.uk

Ivor Dembina’s book, Old Jewish Jokes, and a short documentary film about Millwall Jew can be ordered and watched respectively at www.ivordembina.com